Johnson said he has spoken with lawmakers about similar efforts in Florida, New Jersey, New York and Ohio. The company supported a new California law that prohibits pharmacies from acquiring test strips from any but an authorized list of distributors. Glenn Johnson, general manager for market access at Abbott Diabetes Care, which makes about one in five strips purchased in the United States, said manufacturers lose more than $100 million in profits a year this way, much of it in New York, California and Florida. The insurer reimburses the pharmacy the retail price and then demands a partial rebate from the manufacturer - but it’s a rebate the manufacturer has paid already for this box of strips.

SELLING OUTDATED ACCU CHEK TEST STRIPS FULL

While some resellers use websites like Amazon or eBay to market strips directly to consumers, the biggest profits are in returning them to retail pharmacies, which sell them as new and bill the customer’s insurance the full price.

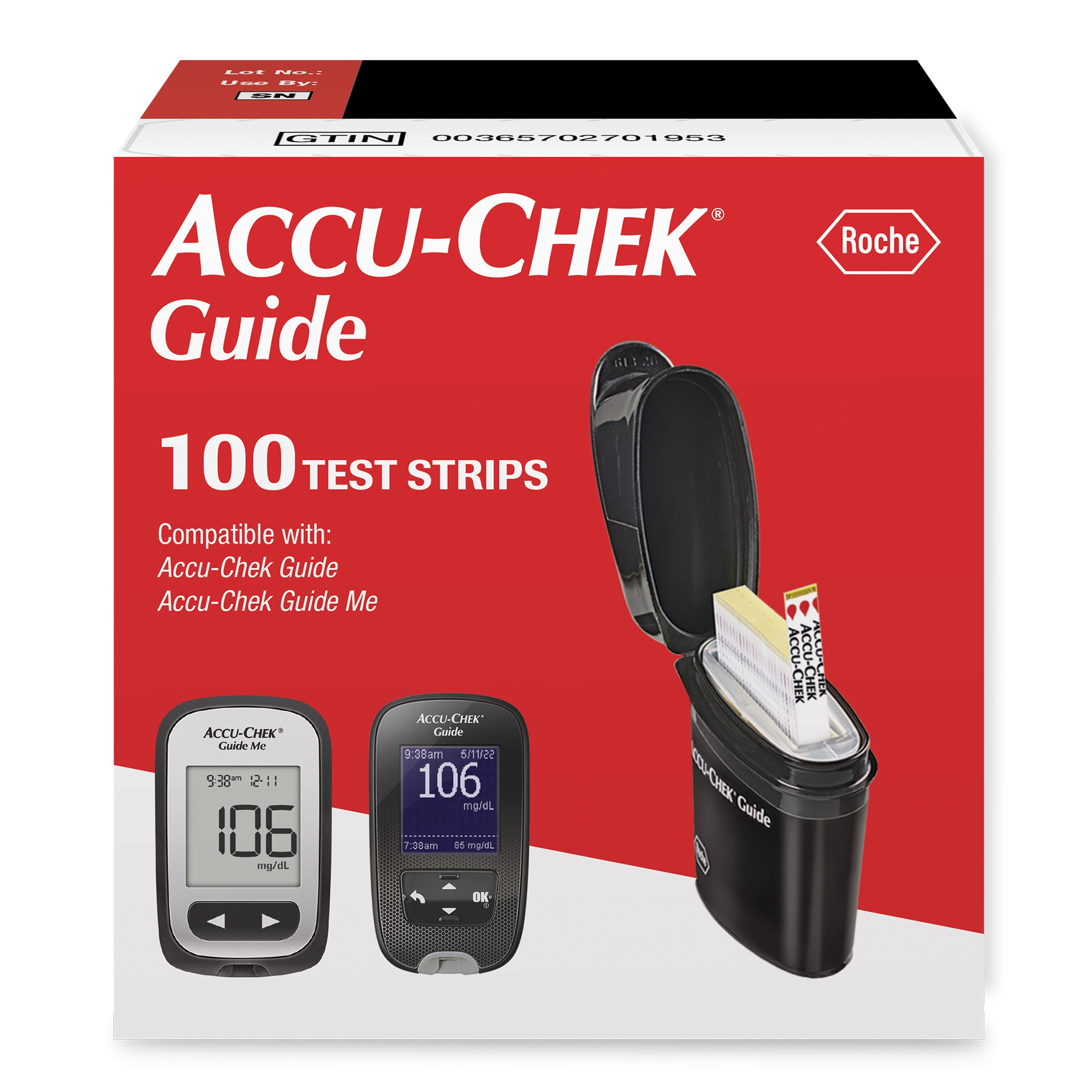

If a patient’s insurer shifts her to a new brand, she must get a new meter, often leaving behind a supply of useless strips. The market glut is also a consequence of a strategy adopted by manufacturers to sell patients proprietary meters designed to read only their brand of strips. ‘It’s a tiny little piece of plastic that’s super cheap to manufacture, and they’ve managed to make a cash cow out of it.’ The Langleys are mainly buying up excess strips from insured patients who have been flooded with them, sometimes even when not medically necessary.Īlthough patients who manage their diabetes with non-insulin medications or with diet and exercise needn’t test their blood sugar daily, a recent analysis of insurance claims found that nearly one in seven patients still used test strips regularly. CVS, by contrast, retails the strips for $164.

SELLING OUTDATED ACCU CHEK TEST STRIPS PLUS

For example, the brothers will pay $35 plus shipping for a 100-count box of the popular brand Freestyle Lite in mint condition.

The amount the Langleys pay depends on the brand, expiration date and condition, but the profit margins are reliably high. Today they buy strips from roughly 8,000 people their third-floor office in Reading, Mass., receives around 100 deliveries a day. He and his twin brother launched the website to solicit test strips from the public for resale. That was the opportunity that caught Chad Langley’s eye.

The middlemen buy extras from people who obtained strips through insurance, at little cost to themselves, and then resell to the less fortunate. Small wonder, then, that a gray market thrives. Also left out are the underinsured, who may need to first satisfy a high deductible.įor a patient testing their blood many times a day, paying for strips out-of-pocket could add up to thousands of dollars a year. But the arrangement leaves the uninsured - those least able to pay - paying sky-high sticker prices out of pocket. These transactions are invisible to the insured consumer, who might cover a copay, at most. Manufacturers set a high list price and then negotiate to become an insurer’s preferred supplier by offering a hefty rebate. The sticker price is the result of behind-the-scenes negotiations between the strips’ manufacturer and insurers. But like most goods and services in American health care, that number doesn’t reflect what most people pay. In a retail pharmacy, name-brand strips command high prices. Unlike the resale of prescription drugs, which is prohibited by law, it is generally legal to resell unused test strips. Some clinicians are surprised to learn of this vast resale market, but it has existed for decades, an unusual example of the vagaries of American health care.

Often the sellers are insured and paid little out of pocket for the strips the buyers may be underinsured or uninsured, and unable to pay retail prices, which can run well over $100 for a box of 100 strips. 116th Street, each strip is also a lucrative commodity, part of an informal economy in unused strips nationwide. More than 30 million Americans have Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes, and most use several test strips daily to monitor their condition.īut at this store on W. Hanging from the awning, a banner reads: “Get cash with your extra diabetic test strips.”Įach strip is a laminate of plastic and chemicals little bigger than a fingernail, a single-use diagnostic test for measuring blood sugar. On most afternoons, people arrive from across New York City with backpacks and plastic bags filled with boxes of small plastic strips, forming a line on the sidewalk outside a Harlem storefront.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)